Camilo Fernández Cozman

Researcher at the Instituto de Investigación Científica (IDIC)

Profile in Cris Ulima

2020 / 08 / 31

Translated from Spanish by Katrina Rebecca Heimark, researcher at the Instituto de Investigación Científica (IDIC) and translator.

A few years ago, I attended an international conference where a speaker attempted to explain the importance of the internet for students in the 21st Century. Basing his argument on the cognitive semantics of George Lakoff and Mark Johnson (2003), he postulated that human thought, for the most part, is of a metaphorical nature. Later, he asked himself about one of the metaphors that dominates the present world, which is “the internet is God.” In other words, the internet solves all our problems and has the most reliable information in the world. Immediately afterwards, the speaker began to refute this metaphor using an army of examples, by explaining why we should question this idea that many uncritically assume in our everyday lives.

The case which I will expound on is the work of Abraham Valdelomar (1888-1919), a Peruvian writer who lived scarcely 31 years, but who wrote over 2,000 pages. Chronicler, playwright, novelist and founder of the Peruvian tale, Valdelomar wrote few but striking poems, and was a decisive influence in the works of Cesar Vallejo. His two most famous poems are: “Tristitia” and “El hermano ausente en la cena de Pascua.” I will focus on this latter text.

El hermano ausente en la cena de Pascua

La misma mesa antigua y holgada, de nogal,

y sobre ella la misma blancura del mantel

y los cuadros de caza de anónimo pincel

y la oscura alacena, todo, todo está igual…Hay un sitio vacío en la mesa hacia el cual

mi madre tiende a veces su mirada de miel

y se musita el nombre del ausente; pero él

hoy no vendrá a sentarse en la mesa pascual.La misma criada pone, sin dejarse sentir,

la suculenta vianda y el plácido manjar;

pero no hay la alegría ni el afán de reírque animaran antaño la cena familiar;

y mi madre que acaso algo quiere decir,

ve el lugar del ausente y se pone a llorar…

(Valdelomar, 1916, pp. 221-222)

The problem I am going to describe corresponds to the title of the poem. A few months ago, a student read an essay of mine about this Valdelomar poem and told me “Professor, you’ve made a mistake with the title of the poem. It is ‘El hermano ausente en la cena pascual’ not ‘El hermano ausente en la cena de Pascua.’” Actually, the error was in his sources, but he didn’t know it and he believed them. In the field of literary research, this is a problem that should be resolved and is not of minimal importance. For example, Vallejo’s book of poems is titled Poemas humanos, not Poemas humanitarios. But in order to prove his hypothesis, said student opened his laptop and showed me some search results that apparently confirmed head-on what he was stating.

Indeed, the poem can be found on the important website of the BBVA Continental that is titled Find your Poem (Fundación BBVA, n.d.), in which illustrious figures—such as Mario Vargas Llosa, Nobel Prize in Literature laureate—read some texts from Peruvian poets. The poem is also included in a blog belonging to the Pontifical Catholic University of Peru which is administered by Jaime David Abanto Torres (2013), in the Modernismo Latinoamericano blog (Biarrubia, 2013), and on the second page of a web archive titled “Recursos Leo Todo” (Plan Lector. Leo Todo, n.d.). All of these websites make the same mistake: ascribing the wrong title to Valdelomar’s poem.

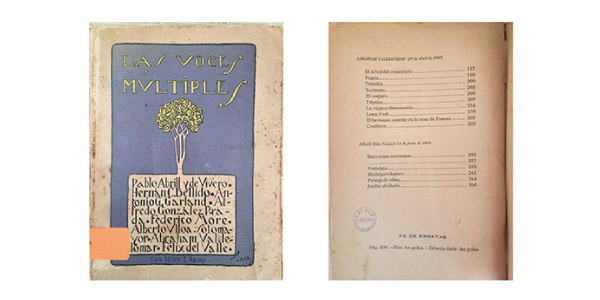

Why is it that with regularity and flippancy this mistake is made, and false information given to the reader? Here my hypotheses; the corresponding edition was not consulted. The poem “El hermano ausente en la cena de Pascua” appears for the first time in the anthology Las voces múltiples, which was published in 1916, including not only Abraham Valdelomar’s poems, but also those of Alfredo González Prada, Federico More, and others. Hence, the mistake spread like wildfire, and thus many trusted the reliability of the source of the information and thus erroneously believed that the aforementioned text was titled “El hermano ausente en la cena pascual.”

Figure 1. Anthology Las voces múltiples (1916).

Umberto Eco (2007) wrote in his article “What is the use of a professor?”:

“Above all, a professor, in addition to instructing, should educate. What makes a class a good class is not that data is disseminated, but that there is a constant dialogue, a confrontation of opinions, a discussion regarding what one learns in school and what comes from outside of it.” (parr. 4)

The Italian semiotician highlights, in this case, that it is fundamental to teach our students to select the most reliable bibliographic sources. Therein lies the formation of new subjects who think freely and learn to live democratically respecting the work of our ancestors.

In this case, it is necessary to briefly discuss three topics in the area of literary research. In the first place, we must evaluate the importance of the exploration of the best bibliographic sources. If a researcher purports to study the poems of Vallejo, they should work with the most trusted edition that also takes other corresponding manuscripts into account. If not, hypotheses cannot be precisely verified, and this will reduce the precision of the analysis. Second, we must compare the different versions of a poem, if the idea is to examine why Vallejo changed the first version of “Masa,” one of the fundamental texts in España, aparta de mí este cáliz, a collection of poems focused on the Spanish civil war. Third, after comparing different editions of the author’s complete poetry, it is indispensable that we choose to work with the best version so that our research is straightforward and can be compared with the poems we have carefully chosen to test our hypothesis based on citations of verses that allow for a particular exegesis. [1]

Creative work is very painstaking and should be valued as it truly is. Thus, the best homage to an author of the stature of Valdelomar is not just to read texts such as “El Caballero Carmelo” or “Los ojos de Judas,” two essential tales, but to also to faithfully store in our memories the titles of his works, as they deserve to be remembered. It’s about respecting our past and building, upon its legacy, a new future.

Recommended reading

Valdelomar, A. (2000). Obras completas. Copé-Petroperú.

| Cite this post (APA, seventh edition) Fernández Cozman, C. (2020, August 31). The importance of reliable primary sources for literary research (K. Heimark, Trans.). Scientia et Praxis: Un blog sobre investigación científica y sus aplicaciones. https://www.ulima.edu.pe/en/idic/blog/the-importance-of-reliable-primary... |

Note

[1] The term “exegesis”, in the field of literary research, refers to the process of interpreting a literary text.

References

Abanto Torres, J. D. (2013, April 16). El hermano ausente en la cena pascual. Jaime David Abanto Torres. Derecho, Literatura, Cine y Música.

Biarrubia, C. (2013, December 30). "El hermano ausente en la cena pascual"- Abraham Valdelomar. Modernismo Latinoamericano.

Eco, U. (2007, May 21). De qué sirve un profesor. La Nación.

Fundación BBVA. (n.d.). El hermano ausente en la cena pascual.

Lakoff, G. & Johnson, M. (2003). Metaphors We Live By. The University of Chicago Press.

Plan Lector. Leo Todo. (n.d.). Recursos Leo Todo.

Valdelomar, A. (1916). El hermano ausente en la cena de Pascua. In P. Abril de Vivero et al., Las voces múltiples (pp. 221-222). Librería Francesa Científica E. Rosay.

Add new comment